A New Paradigm for Solar Energy

By Christopher Toy, Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Soil and Crop Sciences and Trainee in the CSU InTERFEWS Program

Imagine a future in which the bulk of our energy needs are provided by solar generated electricity. Electric cars zip around all over American roads, and perhaps their batteries even contribute to distributed storage. Air pollution levels are lower, electricity is probably even cheaper! Sounds idyllic right? But hold on. Imagine you’re driving that fancy electric car out in the countryside and you notice that the beautiful agricultural landscape looks quite different. With the rise of solar energy, the countryside looks a lot more industrial all of the sudden. The nice pasture with cattle grazing? That’s solar panels now. The field of golden wheat? Solar panels. The rustic old grain silo? Try an electrical sub-station.

The benefits of solar energy are widely touted in the media, but a fact the gets far less attention is that solar energy is spatially extensive. In other words, turning sunlight into electricity takes up a lot of space, and the most desirable land is often agricultural land. Agriculture and solar energy share many of the same needs; wide open, sunny land that has access to transmission lines and isn’t too far from the customer (Adeh et al, 2019). These shared needs mean that conflicts are brewing due to solar energy’s present exponential growth.

In order to understand why these shared needs have the potential to create conflicts, it is first necessary to have some insight into the social and economic history of modern rural America. The industrial revolution, specifically the spread of tractors during the early 1900s, greatly accelerated mechanization of farm labor and enabled one person to do the work that would have required teams of draft animals and hired labor in the late 1800s (Conkin, 2008). Another major development in American agriculture occurred in the time of the Green Revolution during the 1960s. The technologies and policies of the Green Revolution encouraged adoption of modern industrial style agriculture. The most common mantra of this era was “Get big or get out”, with the idea being that farmers using even larger machinery and heavy chemical inputs could manage much larger farms than their predecessors.

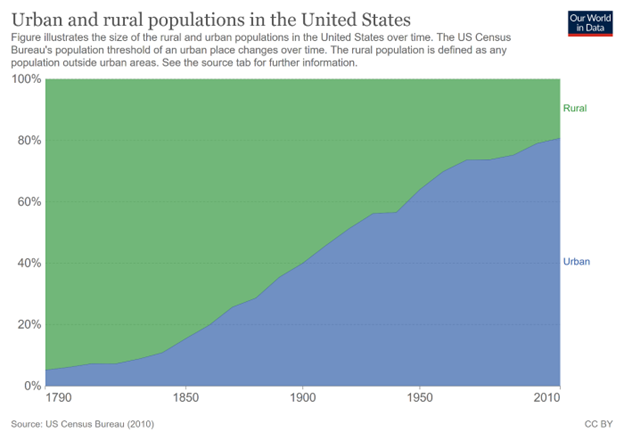

The gradual replacement of human labor with these off-farm inputs and large machinery has steadily displaced jobs in the agricultural sector, leading farm operations to consolidate into ever fewer hands, leaving little to no economic opportunity for those farmers who were unable or unwilling to adopt the industrial model. The end result is that most of these farmers and their families have abandoned rural life for the city in search of economic opportunity.

That brings us to the contemporary American landscape. There are now four Americans living in cities for every rural American (US Census Bureau, 2021) and only about 350,000 farmers that account for 90% of production, compared to 6 million in 1930 (Conkin, 2008). This migration to cities has dramatically changed the nature of day-to-day life for those who remain in the country. Neighbors are fewer and further apart and rural people face long commutes, usually to a Walmart, for supplies instead of the small general stores and informal community trading that characterized the rural economy previously.

With this background of rural demography, it becomes much clearer why a modern farmer might resent and/or resist solar development. It can be viewed as another step forward in the industrialization of the rural economy, furthering rural depopulation and thus weakening a rural way of life. Just as many farmers were forced away due to “get big or get out”, so too farmers are now cutting deals with solar energy developers and putting their land out of agricultural production entirely.

All of this may sound like a lot of doom and gloom for an agrarian lifestyle, but what if there were a way for solar energy and agriculture to actually cooperate rather than antagonize each other?

The answer may lie in a new type of integrated system called agrivoltaics. Agrivoltaics is a combination of the words agriculture and photovoltaics, or solar electricity. The official definition of agrivoltaic systems is still evolving, however there is consensus among scientists who research these systems that it involves growing vegetation within the solar array itself, not merely around the edges or on adjacent fields. This means that growing crops and producing solar electricity doesn’t need to be an either/or proposition. Both modes of production can take place, fully integrated with each other, on the same parcel of land.

Perhaps even more exciting is the growing body of evidence which suggests that there are even synergistic benefits, whereby the solar panels benefit crop production, and the crops benefit solar electricity production. What follows is a discussion of some of these benefits based on recent research.

Water Use Efficiency/Panel Cooling — While we generally think of dry climates as lacking water it is necessary to consider how much sunlight a climate receives in order to understand dryness from a plant’s perspective. A plant in a tropical rainforest doesn’t experience water stress even though the sun is powerful because there is plenty of water for cooling, and an arctic plant doesn’t experience water stress even though it may be quite dry because the sun is not very powerful. Plants experience water stress when there is an imbalance between these two variables, such as when there is not very much water and the sun is also quite powerful. This would describe much of the American West. So, based on how climate types are classified, aridity can be thought of as an excess of sunlight, not just a lack of water.

In arid climates such as Colorado or Arizona the plants grown within a solar array are much more shaded than in an open field. This reduction in solar radiation has been demonstrated to be a milder environment in which many types of plants are able to use what little water they receive more efficiently, thus growing larger or producing more fruit than they would with the same amount of water in an open field (Adeh et al, 2018).

What’s more, as the plants transpire, they don’t only cool themselves off, they cool the solar panels above them as well (Barron-Gafford et al, 2019). This is significant because solar panel efficiency decreases as the panels heat up. By keeping the panels cooler, it is possible to gain modest increases in electric production efficiency.

Pollinator Habitat — Another option for agrivoltaic systems is to grow native vegetation beneath the panels instead of agricultural crops. This is a more hands-off approach with the goal of benefitting nearby agricultural crops by providing habitat for beneficial animals such as pollinators or insects that prey on pests. This is similar to existing programs that encourage farmers to plant borders of native vegetation around their fields or to restore portions of their fields to native prairie.

While not production agriculture, this type of agrivoltaic system still fits in well in an agricultural landscape. It “plays nicely” with agriculture so to speak, and thus should still function to ease tensions between farmers and solar developers. A recent model showed that if all existing solar arrays were to have native vegetation planted beneath them, over 800,000 acres of flowering crops could benefit from enhanced pollination. If the California almond industry alone were to see a 1% increase in pollination, the result would be a $4 million increase in almond production (Walston et al, 2018).

Shade for grazing animals — Another common type of agriculture, especially in Western states, is livestock grazing on pasture or rangelands. This setting would have the same water-use efficiency benefits described above, enabling more plant growth with the same amount of water. There is additionally a benefit to the sheep or cattle as well. Much as the plants benefit from shade in a climate with harsh sunlight, so too the livestock are able to regulate their temperature more easily when they have shade to protect themselves from the sun. Heat Stress has been linked to decreased feed intake and body weight gain, reduced reproductive efficiency, and altered meat quality (Johnson, 2018). Reducing heat stress ultimately translates to healthier animals with a higher standard of living.

These examples of potential synergistic benefits of agrivoltaic systems are hopefully just the beginning of what there is to learn about this novel type of agriculture/energy co-production. It is my sincere hope that this article reaches some farmers and energy developers and inspires them to try something new.

As farmers are the real creative powerhouse in agriculture, we will only realize the full potential of agrivoltaics once farmers begin to experiment with it on their own lands. For now, I am continuing research on agrivoltaics in Colorado and eagerly watching for the next creative innovation to spring forth from the farming community.

About the Author:

Christopher Toy is a graduate student in the Agroecology Lab at Colorado State University, advised by Dr. Meagan Schipanski. His research focuses on how to understand the functions of agrivoltaic systems using an ecosystem services framework. He can be contacted at his email, [email protected].

Works Cited

Conkin, P. K. (2008). A revolution down on the farm : the transformation of American agriculture since 1929 . University Press of Kentucky.

Hassanpour Adeh, E., Selker, J. S., & Higgins, C. W. (2018). Remarkable agrivoltaic influence on soil moisture, micrometeorology and water-use efficiency. PLOS ONE, 13(11), e0203256. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203256

Adeh, E. H., Good, S. P., Calaf, M., & Higgins, C. W. (2019). Solar PV Power Potential is Greatest Over Croplands. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47803-3

Barron-Gafford, G. A., Pavao-Zuckerman, M. A., Minor, R. L., Sutter, L. F., Barnett-Moreno, I., Blackett, D. T., … Macknick, J. E. (2019). Agrivoltaics provide mutual benefits across the food–energy–water nexus in drylands. Nature Sustainability, 2(9), 848–855. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0364-5

Johnson, J. S. (2018). Heat stress: Impact on livestock well-being and productivity and mitigation strategies to alleviate the negative effects. Animal Production Science, 58(8), 1404–1413. https://doi.org/10.1071/AN17725

United States Census Bureau. (2021, March 30). Urban Areas Facts. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/urban-rural/ua-facts.html

Walston, L. J., Mishra, S. K., Hartmann, H. M., Hlohowskyj, I., McCall, J., & Macknick, J. (2018). Examining the Potential for Agricultural Benefits from Pollinator Habitat at Solar Facilities in the United States. Environmental Science and Technology, 52(13), 7566–7576. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b00020